Are Southern Heritage Sites Under Attack? A Closer Look at Recent Fires and Rising Concerns

Nottoway Ignites Deeper Questions

By The Bayou Insider Staff

The May 15 fire that devastated Louisiana’s famed Nottoway Plantation—the largest remaining antebellum mansion in the South—was more than just a tragic loss. It was a signal flare across our heritage. One of the most iconic and architecturally significant landmarks in the South was reduced to rubble in a matter of hours. The grand white columns, the intricate molding, the preserved museum artifacts—gone in smoke and ash.

As flames tore through the structure, many across Louisiana and the broader South couldn’t shake the feeling that this wasn’t just an accident. It didn’t feel random. It felt symbolic.

And it’s not the first time.

Fires like this have become disturbingly common across the Southern United States in recent years. Historic churches dating back to Reconstruction. Plantation homes that give us a glimpse into the past. Civil rights landmarks that once hosted marches and sermons. Outbuildings that housed generational tools, records, and heirlooms. One after another, they’ve gone up in flames.

Each time, we’re told: “It’s under investigation.”

Each time, we hear: “It may have been electrical.”

But each time, the deeper question lingers:

Is someone trying to burn away our past?

These are more than buildings. They are touchstones—physical connections to who we are, where we came from, and what we must never forget. And if this is a coordinated effort—or even a cultural climate that fosters neglect and hostility toward our own heritage—then we are not just losing structures.

We’re losing our story.

Recent Fires That Demand Closer Attention

These aren’t forgotten barns or abandoned buildings. These are places of memory, faith, and meaning. Below are just a few of the most prominent fires in recent years—each one striking at the heart of a community, a legacy, or a chapter in Southern history.

Nottoway Plantation (White Castle, LA – 2025)

Built in 1859, Nottoway stood as the largest surviving antebellum mansion in the South, a striking symbol of Louisiana’s architectural and cultural past. With 64 rooms, spanning over 53,000 square feet, it drew tourists from around the world who wanted to walk its storied halls and witness firsthand the grandeur of the Old South.

On May 15, fire broke out in a second-floor museum bedroom. Within hours, the roof collapsed, and much of the structure was destroyed. Museum artifacts—many one-of-a-kind—were likely lost. The fire rekindled later that evening, further devastating the site. Though investigators are working to determine the cause, the loss has already dealt a major blow to Louisiana’s heritage tourism and historical preservation efforts.

Clayborn Temple (Memphis, TN – 2025)

Constructed in 1892, Clayborn Temple was a cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement and one of the most historically significant churches in the United States. It served as the staging ground for the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, famously supported by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In April 2025, fire tore through the sanctuary as the church was undergoing active restoration. The damage was extensive, prompting new concerns over the security and vulnerability of civil rights-era landmarks. Though an investigation is still underway, the loss has already been felt across Tennessee and beyond. A place of peace and protest—scarred by fire once again.

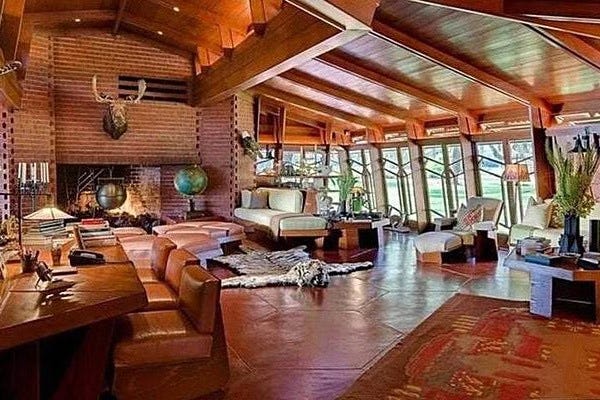

Auldbrass Plantation (Yemassee, SC – 2024)

A rare Southern masterpiece by Frank Lloyd Wright, Auldbrass is a National Historic Landmark blending modernist vision with Lowcountry heritage. In October 2024, a fire destroyed one of the estate’s original outbuildings.

The blaze caused an estimated $2 million in damage and destroyed two rare Lincoln Continentals once owned by Wright himself. The South Carolina Law Enforcement Division’s Arson Unit was called in to investigate. Though the main house was spared, the fire was a wake-up call about the fragility of even well-maintained historic properties.

Mosquito Beach Historic District (Charleston, SC – 2022)

Known as a cultural haven for the local African American community during segregation, Mosquito Beach was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2020. Its most iconic structure, the Pine Tree Hotel, was central to that story—a gathering place for generations.

In April 2022, the building was destroyed by fire under “suspicious” circumstances. Investigators found footprints near the site, but no suspects were identified. The community continues to mourn the loss of this irreplaceable gathering place and symbol of local resilience.

Mount Pleasant Black Churches (Opelousas, LA – 2019)

Between March and April 2019, three historic Black churches—St. Mary Baptist, Greater Union Baptist, and Mount Pleasant Baptist—were burned to the ground. The arsonist, Holden Matthews, was the son of a St. Landry Parish sheriff’s deputy. His motivations were reportedly tied to extremist anti-Christian ideology and dark subcultures that glorify destruction.

Matthews was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in federal prison. The churches, many of which dated back to the late 1800s, were cornerstones of their communities—built by freedmen, led by pastors who shepherded generations through times of both peace and persecution.

Looney House (Ashville, AL – 2022)

Built in 1818, the Looney House was one of Alabama’s oldest surviving residential structures and a tangible piece of early American frontier life. It had served as a museum and historic attraction, preserving tools, furnishings, and stories from the pre-Civil War era.

In August 2022, fire gutted the home in what law enforcement later confirmed was arson. The destruction of the house was not just a loss to Ashville—it was a blow to the state’s preservation efforts and a reminder of how quickly centuries of history can vanish in flames.

Is There a Pattern—or Just Coincidence?

While not every fire on this list has been officially ruled as arson, a growing number of them involve arson task forces, criminal investigations, or circumstances labeled “suspicious” by authorities. That alone should raise red flags. These are not routine electrical fires in vacant buildings. These are deliberate attacks, or at the very least, acts of neglect toward sites that represent a region’s heritage, identity, and spiritual memory.

We are living in a time of extreme polarization, where historical narratives are being rewritten in real-time and symbols of the past are being vilified, defaced, or erased. In such a climate, the question must be asked:

Are historic sites in the South—especially those tied to Christian faith, traditional values, or Southern heritage—being targeted, either ideologically or intentionally?

It’s a question that makes many uncomfortable, but ignoring it only emboldens the forces working to undermine the past. Fires don’t just destroy property—they break chains of memory. They eliminate the places where stories were lived, where generations gathered, and where truths—complex as they may be—are anchored in brick, wood, and stone.

Whether it’s overt arson, coordinated attacks, or a cultural atmosphere that breeds disregard for tradition, one thing is clear:

This is no longer coincidence. It’s a pattern.

And patterns demand vigilance.

Cultural Sites, Political Symbols, and the Battle Over Memory

Southern landmarks are more than structures—they are legacies. These sites represent craftsmanship, community identity, and a connection to the generations who built the South. While the broader culture may attempt to politicize or erase these landmarks, many Louisianans—and Southerners at large—see them as reminders of family history, faith, perseverance, and place.

Unfortunately, in today’s divisive climate, these sites can become collateral damage in ideological battles. As debates over monuments and memory grow louder, it’s increasingly clear that efforts to preserve our shared cultural heritage are under threat—not because of what these places are, but because of what others claim they represent.

Rather than erasing history, we should be striving to understand it fully—celebrating what is noble, acknowledging what was broken, and refusing to let modern revisionism burn down the past.

Cultural Marxism and the War on Heritage

While each fire may appear isolated, we would be foolish not to consider a deeper pattern. Across the South—and increasingly across the entire nation—there is a sustained and strategic effort to dismantle the cultural foundations that bind us. This is not merely political division. It is the quiet advance of Cultural Marxism—an ideology that seeks to erase faith, family, history, and national identity in order to replace them with a progressive, globalist worldview.

We see this clearly in the way Southern history is constantly demonized. Monuments are removed. Names are changed. Entire chapters of our past are reduced to caricature or erased altogether. And now, physical sites—homes, churches, plantations, museums—are burning. Whether by neglect, sabotage, or design, our heritage is under attack.

This is not just a Southern issue. It is an American issue. But Louisiana, with its deep roots, diverse heritage, and fiercely independent spirit, stands on the front lines. We are not just preserving old buildings—we are preserving the soul of a people. And in an age of engineered amnesia, that is a revolutionary act.

America is in an ideological war for cultural and historic preservation. So is Louisiana. It is a war we did not ask for—but it is one we must win.

Preservation in the Crosshairs

Regardless of motive—whether these fires are the result of deliberate attacks, criminal negligence, or cultural apathy—they reveal a sobering reality: we are woefully unprepared to protect the historical heart of the South.

Many of these structures, while admired and visited, are not truly defended. The romantic vision of plantation homes, historic churches, and Civil War-era buildings often hides a harsher truth behind the facades: aging wood, outdated wiring, and little-to-no fire prevention infrastructure.

Consider the facts:

Few historic sites are equipped with modern fire suppression systems. Many are made of century-old timber, surrounded by flammable materials, and lack internal sprinklers or sensors due to cost or preservation restrictions.

Security is often minimal. Some properties rely on volunteers or part-time staff. Others sit quietly in small towns with no cameras, no monitoring, and no consistent patrols.

Funding for maintenance and restoration is limited—or tied up in red tape. Grants are competitive. Donations are inconsistent. Government priorities often push culture to the back of the line.

The result? These historic treasures—rich with generational value, spiritual weight, and architectural beauty—are left increasingly exposed to accident, vandalism, or malice.

It’s not just a matter of sentiment. The economic impact is real. Heritage tourism is a multi-billion-dollar industry in the South, and Louisiana depends on it. Every site lost is a blow to local economies, civic identity, and our shared historical consciousness.

In short: if we don’t take preservation seriously now, there won’t be much left to preserve in the years to come.

What Should Be Done?

If we’re serious about defending the South’s historical and cultural identity, we must stop reacting to tragedy—and start preparing for prevention. The preservation of our past cannot be passive. It must be intentional, proactive, and principled. Here’s what must happen:

Investigative Oversight

State legislatures must require full transparency and accountability in all investigations involving fires at historic sites. That means immediate public disclosure of fire origins, release of forensic findings, and zero tolerance for bureaucratic foot-dragging. If something criminal occurred, the public deserves to know. If negligence played a role, someone must answer for it. Anything less allows cultural destruction to go unchecked.

Protective Funding

Both federal and state governments must prioritize the protection of heritage sites—not just as tourist attractions, but as cultural assets vital to our identity. Expanded grant programs, tax credits for private historic site owners, and emergency repair funds should be established. If we can fund modern art installations and urban development programs, we can afford to save the buildings that tell the story of who we are.

Cultural Education

It’s not enough to preserve physical structures—we must also preserve meaning. Our children, our communities, and our elected officials need to understand why these places matter. Not because they’re perfect, but because they’re honest. The story of the South is complex, rich, and worth telling. When we teach history in full—warts and all—we fight back against efforts to reduce heritage to a political weapon.

Community Watch Programs

No one will fight for your town’s courthouse, chapel, or historic home like you will. Local communities must be empowered to form preservation task forces, historical patrols, or neighborhood watches that monitor and report suspicious activity. Preservation is not the government’s job alone—it is a shared responsibility. And it starts at the grassroots.

We must protect what remains, restore what is lost, and remind each generation why it all matters. Because once the flames are gone and the headlines fade, the only thing that will preserve the past—is us.

Conclusion: Fire Is a Weapon—and a Warning

History is not just something we read in books. In the South, it’s something we walk through. It’s etched into the wood of plantation homes, carved into the steeples of country churches, and laid brick-by-brick in courthouses, schools, and family cemeteries. It’s physical. Tangible. Sacred.

So when those structures burn, it’s not just an architectural loss—it’s a blow to our identity. Something deeper is threatened: our memory, our heritage, our right to remember.

The recent fires—Nottoway included—are more than tragic accidents or unfortunate coincidences. They are warnings. Warnings that our enemies are not always visible. That neglect, ideology, or deliberate destruction can erase in hours what generations took centuries to build. And if we’re not vigilant, we’ll wake up one day and realize we’ve handed our legacy over to silence, rubble, and revisionist history.

We must ask not just what happened, but why—and more importantly, what we’re going to do about it.

We are not victims of history. We are stewards of it.

And the flames, though devastating, have one last purpose: to awaken us before it’s too late.

Sources:

🔥 Stand Up Before More Falls Down

The fires are real. The losses are mounting. And the silence is deafening.

Our past is under siege—not by accident, but by neglect, ideology, and indifference. If we don’t act now, our children will inherit ruins instead of roots.

Here’s how you can fight back:

Share this article with friends, family, and local leaders. Start the conversation.

Call your state and local officials—demand funding and protection for our historic sites.

Support a local preservation group or start one in your town.

Speak up—online, at school board meetings, in your community.

Pray. Prepare. Preserve. This is about more than buildings. It’s about identity, legacy, and truth.

🛑 Don’t wait for another headline. Be the reason history stands.

Why We’re Doing This—and What Comes Next for The Bayou Insider

I sat down to write this post with a full heart.