The Louisiana Purchase Part 2 - Mapping a Nation: Surveying the New American Frontier

This is the second installment of a 7-Part Weekly Series on The Louisiana Purchase

By The Bayou Insider Staff

In 1803, the ink had barely dried on the Louisiana Purchase when a pressing question emerged: What, exactly, had the United States just bought?

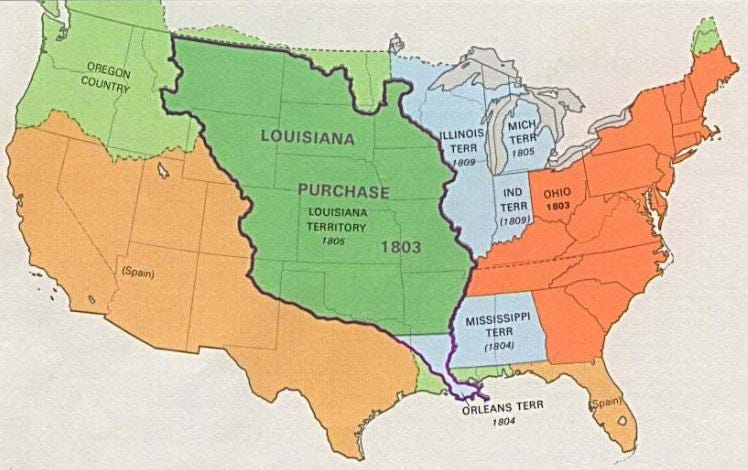

The agreement with France had more than doubled the size of the young republic, adding an astonishing 828,000 square miles to the national domain. From the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, and from the Gulf Coast to the Canadian border, the newly acquired territory was a breathtaking mix of wilderness, towering mountain ranges, winding river systems, fertile plains, dense forests, and unknown frontiers.

But there was one major problem: no one really knew what was out there.

Much of the land was unmapped, undefined, and ungoverned. There were no official borders. No detailed surveys. No road systems. Entire regions were still dominated by Native American nations with their own complex histories, alliances, and claims. Even the French, who had just sold the land, had only loosely administered it in recent years.

To American leaders—especially President Jefferson—the purchase represented a monumental diplomatic victory. But that victory came with a logistical and political challenge: transforming a massive and mysterious expanse into something usable, navigable, and governable. It was one thing to buy land. It was another to understand it, measure it, and manage it.

Acquiring the territory was a bold step. Making sense of it was a national necessity.

The Problem with Boundaries

While the Louisiana Purchase looked clean on paper, the reality on the ground was far more complicated. The treaty between the U.S. and France may have transferred ownership of the land, but it didn’t come with precise maps, marked borders, or even a universally agreed definition of what “Louisiana” included.

The French themselves had only loosely administered much of the territory, and large parts of the region were terra incognita—unknown lands still claimed, used, or inhabited by others. Spain, in particular, disputed the western boundaries of the Purchase, especially in Texas and the Southwest, arguing that France had no right to sell land it had previously ceded to Spain and never fully reclaimed.

Even within the United States, there was confusion. Did the Purchase include the Floridas? What about West Florida, which Spain still held? Where, exactly, did the Mississippi River territory end and Spanish claims begin? These weren’t academic questions—they were the kinds of issues that could trigger diplomatic incidents or even war.

Meanwhile, Native American nations—from the Osage to the Comanche—had their own deep-rooted territorial claims, trade routes, and political systems. To them, treaties between European powers were irrelevant. The U.S. might claim the land on paper, but in reality, much of it remained beyond federal reach or control.

Without defined borders, surveyed plots, or enforceable land titles, the government couldn’t sell the land, defend it, or even govern it effectively. Chaos loomed on the horizon if something wasn’t done quickly to impose order.

Jefferson and his administration realized that to fully secure the purchase—and to prepare it for settlement, trade, and statehood—they would need more than ink and diplomacy. They would need men with compasses, chains, and courage to bring shape to the unknown.

Surveyors: America’s Quiet Frontline

In the wake of the Louisiana Purchase, the federal government faced an urgent challenge: how to turn an abstract land deal into a functional part of the republic. The answer didn’t lie with generals or politicians—it lay with surveyors, the unsung figures who would define the American landscape one mile at a time.

These men weren’t widely known, but they were essential. They served as scientists, scouts, and civil engineers, often at the same time. Their work was tedious, dangerous, and frequently lonely. Yet without it, land couldn’t be sold, taxes couldn’t be collected, and towns couldn’t be built.

Armed with compasses, measuring chains, sextants, and rudimentary astronomical tools, surveyors fanned out across the wilderness to divide the land using the Public Land Survey System (PLSS)—a grid-based method of organizing the country into townships (6 miles by 6 miles), then subdivided into sections (640 acres each) and quarter-sections. This system brought uniformity and legal clarity to what had previously been a vast, undefined frontier.

They marked boundaries by placing wooden stakes, carving trees, or creating piles of stones—simple but effective indicators of where one property ended and another began. These early markers, often driven into the soil hundreds of miles from the nearest city, would form the legal foundations of American land ownership for generations.

But this work was not for the faint of heart.

Surveyors endured sweltering heat, bitter cold, wild animals, disease, and rugged terrain. They traversed swamps, crossed rivers, and scaled ridgelines, often with limited supplies and only a vague idea of what lay ahead. In some areas, they encountered resistance from Native American tribes rightfully suspicious of government agents carving up ancestral lands.

Some surveyors were veterans of the Revolution or trained engineers, while others were self-taught frontiersmen with natural skill and grit. What united them was a shared role in shaping the physical and legal identity of the United States.

Though they rarely made headlines, these quiet pioneers laid the groundwork—quite literally—for everything that came after. Farms, towns, railroads, and even state lines would emerge from the measurements and marks they left behind.

Meridians and Baselines: The Nation’s Measuring Tape

To make order out of chaos, the United States needed a framework to organize the new territory systematically. That framework came in the form of principal meridians and baselines—the invisible lines that would define how America divided, measured, and distributed land across the western frontier.

These weren’t merely lines on a map. They were the backbone of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS). Meridians ran north to south, and baselines ran east to west. Where they intersected, surveyors established fixed points from which all subsequent measurements would begin. These reference lines ensured that land parcels could be laid out uniformly, regardless of terrain or location.

One of the most important of these early frameworks was the Fifth Principal Meridian, established in 1815. It began just east of the Mississippi River in present-day Arkansas and became the foundational reference point for surveying much of the newly acquired land. Its influence extended into what would become Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, North Dakota, and beyond. Even today, property deeds in many of these states still reference this meridian.

Surveying teams working from the Fifth Principal Meridian would lay out a checkerboard of townships and sections, which allowed the government to sell land to settlers, grant military bounties, and allocate land for schools and infrastructure.

But establishing these meridians and baselines was no small feat. Surveyors had to contend with dense forests, open plains, and rugged terrain—using only basic instruments, celestial observations, and sheer persistence to stay on course over hundreds of miles. Precision mattered. A small miscalculation at the starting point could lead to major discrepancies over time, creating property disputes and legal confusion.

Despite these challenges, the PLSS—anchored by meridians and baselines—brought a sense of mathematical order to geographic vastness. It allowed for one of the most ambitious land management systems in history, transforming untamed frontier into organized potential.

In many ways, these early survey lines were the first drafts of modern America’s map—quietly shaping how the country would grow, govern, and inhabit its new land.

Rivers and Landmarks: Nature as a Guide

While the gridlines of the Public Land Survey System brought structure to much of the western frontier, natural landmarks often served as the first and most reliable guides. Before the lines were drawn with chains and compasses, rivers, ridgelines, and mountain ranges shaped how explorers, traders, and even governments understood the land.

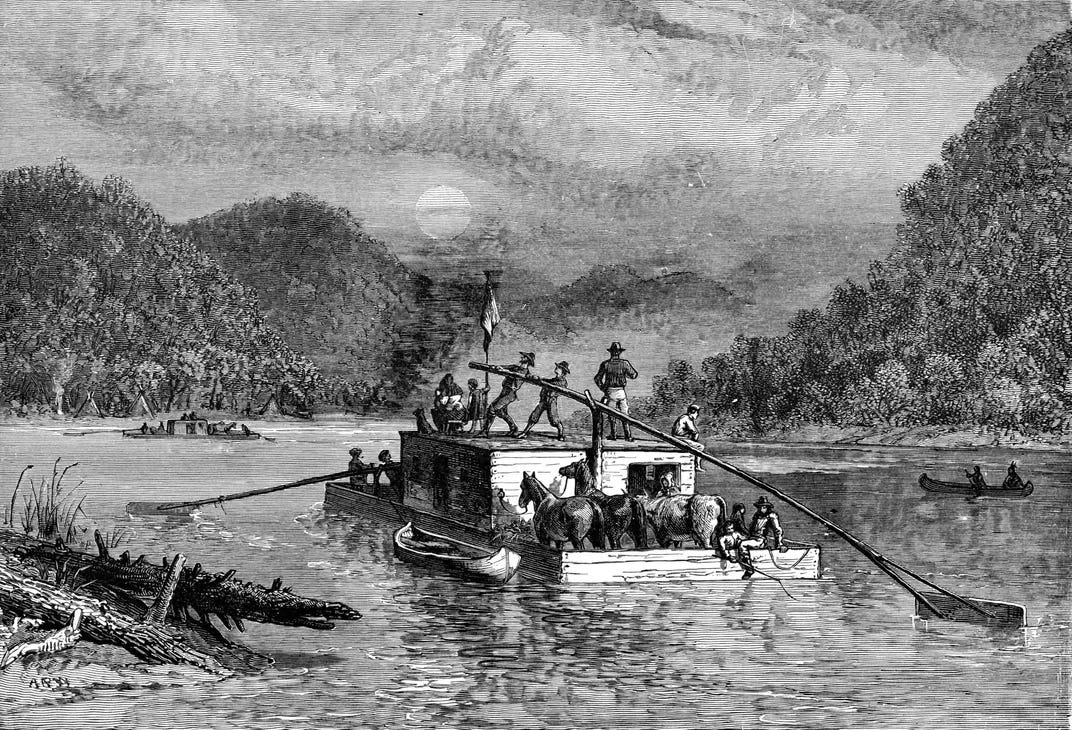

Among the most important was the Mississippi River—the lifeblood of the American interior. It wasn’t just a trade route; it was a geopolitical dividing line. The river marked the eastern edge of the Louisiana Territory and had long been a strategic concern for U.S. leaders. Gaining control of it—and the port of New Orleans—was one of the original goals of Jefferson’s diplomatic efforts in France. With the Purchase, the river became an American highway, carrying goods, people, and ideas deep into the continent.

Further west, the Missouri River became a central corridor of exploration and navigation. When Lewis and Clark set out in 1804, they used the Missouri as their main route through the vast, unmapped interior. Its twists and branches guided them across plains and into the Rocky Mountains, and it soon served the same purpose for trappers, settlers, and future surveyors.

Surveyors often leaned on these natural features as boundary markers. When the terrain became too challenging for precise grid work—or when landmark-based boundaries were deemed more practical—rivers, creeks, and ridgelines were used to define property lines and even state borders. For example, the Sabine River would eventually help form the boundary between Louisiana and Texas.

Yet nature had its quirks. Rivers changed course, especially in flood-prone regions like the Mississippi Delta. This could create disputes, with landowners unsure whether their properties were in one state or another. Still, these features offered something the earliest survey teams lacked: fixed, visible reference points in a landscape otherwise full of uncertainty.

In time, these natural landmarks not only guided settlers—they shaped migration routes, influenced where towns formed, and determined the placement of roads, forts, and trade hubs. For many Americans, their first impression of the Louisiana Territory wasn’t drawn on a map. It was seen from the banks of a river or the base of a hill, etched in nature itself.

The Price of Inaccuracy

In a newly acquired wilderness stretching across nearly a third of the continent, even small errors could have big consequences. Early maps of the Louisiana Territory were often riddled with inaccuracies—some due to technological limitations, others due to pure speculation.

Before formal surveys began, many maps relied on secondhand reports from fur traders, Native guides, or earlier European explorers. These maps frequently included phantom rivers, nonexistent mountain ranges, and vast blank spaces labeled with little more than “unexplored.” Some maps depicted a direct water route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean—a mythical “River of the West” that would eventually be disproved by the Lewis and Clark expedition.

These inaccuracies weren’t just cartographic curiosities. They shaped decisions, settlements, and even diplomacy. Misplaced borders could lead to land disputes between settlers, conflicts between states, or tensions with foreign powers. In areas where boundaries were poorly marked or misunderstood, multiple land claims might be filed on the same parcel, leading to lawsuits—or in some cases, violence.

The consequences could also be financial. Speculators who purchased land based on flawed maps often found their investment was not what it seemed—either too rocky for farming, too remote for transport, or already claimed by someone else. As a result, confidence in the U.S. land system could falter unless the government could prove its ability to measure, map, and manage its new holdings reliably.

This is precisely why Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark west—to gain not just diplomatic relationships and scientific knowledge, but to correct the record. Their expedition provided more than a thrilling tale of adventure—it brought the kind of firsthand data that enabled future surveyors to work with greater accuracy and purpose.

Still, inaccuracies would continue to haunt the westward push for decades. In many places, land surveys were rushed, underfunded, or conducted with outdated tools. Survey lines drawn quickly on paper would later clash with the reality of rivers shifting, terrain changing, or prior settlements being overlooked.

In the grand story of the Louisiana Purchase, it wasn’t just soldiers or politicians who shaped the land—it was the quiet precision (or imperfection) of surveyors’ lines that decided where fences were built, where counties were drawn, and who could call a place home.

Why It Mattered

Surveying the Louisiana Territory may not have captured the public’s imagination like the signing of the treaty or the tales of Lewis and Clark, but it was no less vital. In many ways, it was the invisible infrastructure of American expansion—the quiet foundation on which the future of the nation would be built.

Without surveys, the land could not be sold, settled, or governed. The federal government depended on land sales to help finance operations and pay down national debt. Settlers, many of whom had risked everything to move west, needed clear titles to build homes, plant crops, and defend their claims. And officials at every level needed boundaries to establish jurisdictions, build roads, assign taxes, and enforce laws.

Surveying also gave life to Jefferson’s vision of an “empire of liberty.” He believed that a republic could only survive if it rested on a foundation of independent landowners—citizens who had a personal stake in the land and the freedom to shape their own future. The orderly, gridded divisions created by the Public Land Survey System made that possible. Instead of chaos, there was clarity. Instead of speculation and violence, there was (in theory) fairness and legal order.

In short, surveying transformed raw territory into a working nation.

Moreover, it allowed for long-term planning. School lands were set aside in every township, railroads later followed surveyed corridors, and states could be formed with organized boundaries. Even today, the legacy of those early surveyors is etched into the American landscape—from property deeds to state lines, from fence posts to interstate grids.

What often went unseen by history’s spotlight was, in fact, one of the most essential acts of state-building in U.S. history.

A New National Blueprint

The Louisiana Purchase opened the door to America’s future—but it was the work of surveyors that laid down the blueprint. While diplomats struck the deal and explorers charted the path, it was the measured footsteps of survey crews, cutting lines through forests and across plains, that turned dreams into deeds and wilderness into property.

Each township measured, each section recorded, and each boundary marked created a tangible framework for a growing republic. The grid imposed not just physical order, but civic structure. Where the survey lines went, governance followed—roads were built, counties were drawn, and courthouses rose.

This was more than bureaucracy. It was a statement of national intent. It declared that this land was not merely owned—it was planned, purposed, and promised to the generations to come.

The surveying of the Louisiana Territory wasn’t just a cartographic achievement. It was an act of nation-building. It enabled commerce, encouraged migration, diffused political power beyond the coastal elites, and ultimately knit together a patchwork of states into a unified nation.

Even today, the imprint of this effort is visible in the straight county lines of the Midwest, the checkerboard fields seen from airplane windows, and the legal descriptions on every deed. The land became the canvas, and the surveyor’s tools were the pen that drew America’s future.

In the next installment of The Bayou Insider’s Louisiana Purchase Series, we’ll explore the international consequences of that expansion—how a single transaction in Paris echoed through the halls of power in Spain, Britain, and beyond.

📚 Sources & Further Reading

💬 Enjoyed This Article? Follow the Series.

If you're enjoying our deep dive into the Louisiana Purchase, make sure to:

📬 Subscribe to The Bayou Insider for future installments

🔁 Share this article with history lovers and curious minds

💬 Join the conversation in the comments

Next up: "Diplomatic Ripples—How the Purchase Shook Europe and Spain."